Today, especially in the U.S., parents are giving their babies more unusual, uncommon, and creative names. But not too long ago, family names were the norm – first names passed down from generation to generation, maternal surnames used as middle names, and more. In genealogical research, these “old-fashioned” naming patterns help us to determine family structures.

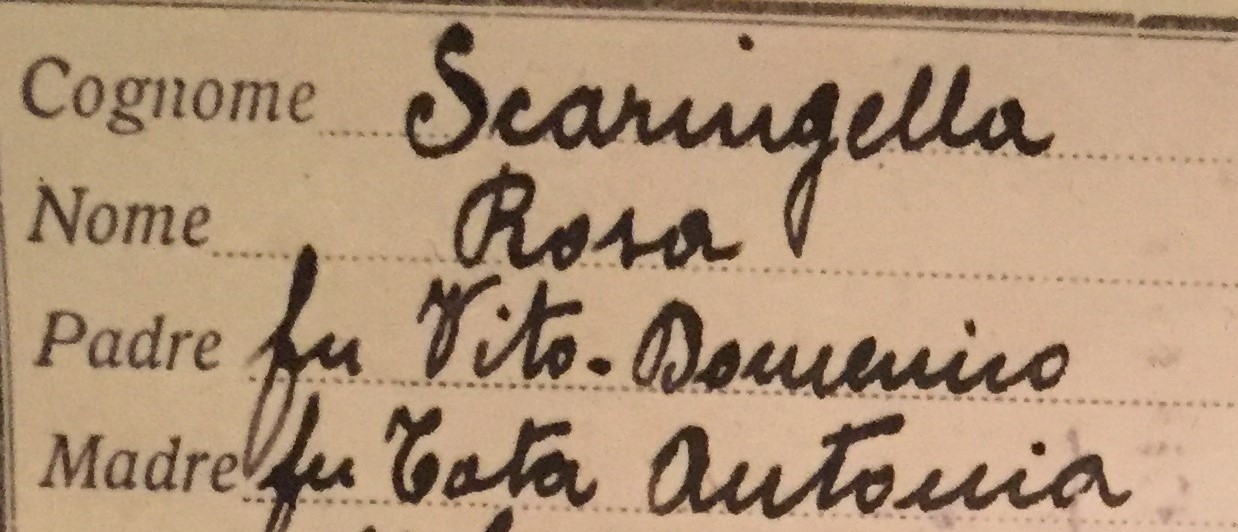

Naming traditions vary from country to country. It is important to understand the different systems in the country your family hails from when building family relationships. When I first began researching my Italian ancestors in Puglia, I discovered many children on the family tree with the same given name. The general practice was to name the firstborn son after the paternal grandfather and the firstborn daughter after the paternal grandmother; second son after the maternal grandfather and second daughter after teh maternal grndmother. This pattern existed not only in my direct line of great-grandparents, but also in the families of their siblings which meant that many children in the same generation had identical given names. To confuse the issue even further, if a child died young, the very next son or daughter born was given the same name until a child with that name lived. In my great-granduncle’s family for example, sadly there were four babies given the name Vitantonio and two with the name Benedetta. It is easy to confuse family relationships, so careful research of vital records is crucial.

Also, in Italy (as in some other cultures), women keep their surname (the name of their father) for their entire lives, even after marriage. This practice actually makes it easier to locate and trace female ancestors in Italy than in many other countries.

In Spain, people do not have middle names but everyone must have two surnames. The naming structure is a given name followed by the paternal family name (inherited from the father who inherited it from his father) followed by the maternal family name (inherited from the mother who inherited it from her father.) For example, the son of Juan Sanchez Garcia and Maria Torres Lopez would be named Carlos Garcia Torres. I recently discovered this naming pattern when researching an artist of Spanish descent. For several years, he was listed on various records with the two surnames used interchangeably.

Scandinavian countries also have a unique pattern based on the “patronymic” system established in 1726. Surnames are derived from the father’s first name. In Sweden for example, the sons of Jens Larsson would be given the surname of Jensson (the son of Jens) and the daughters would be Jensdotter (the daughter of Jens). Most Swedish surnames are patronymic, though they can also be based on nature or a geographic location (more common in Norway and Denmark).

In China (and other Asian countries), naming patterns are very different from Western cultures, and names also have special meanings, depending on the characters used to write the name. The family name (surname) usually consists of one syllable, like Chen. The surname is followed by the given name, which can often contain two names, like Jing and Yi. The baby’s name would then be Chen Jingyi. Women also retained their family names throughout their lives.

There are many other cultural examples – these are just a few to illustrate how important it is to understand the naming system in the country of origin. This will save you many hours of chasing individuals who are not related to you! And then there are nicknames . . .

Such a great summary of naming traditions and the challenges faced when conducting historical or genealogical research. Thank you! Interesting how these traditions often continue a generation or so after, say, immigrating from Europe to the U.S. in the early 20th century, only to fade like other ‘old country’ traditions in the next generation or so.

On a related point, you mention nicknames…I have encountered similar naming conventions among the Irish who immigrated to Michigan’s Beaver Island. I never did a deep dive, just remember how many members of the same family line would have the same given names. It seems that there was no real confusion during their lifetimes, because they were distinguished with nicknames. For example, if there were numerous ‘Pats’ (for Patrick), family stories, photos, and oral histories would use nicknames-often adjectives- like ‘Big Pat,’ ‘Black Pat,’ ‘Little Pat,’ etc. Of course, that doesn’t help much when viewing official documents…!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is excellent information to have in researching the names of relatives who have immigrated from countries that have different naming traditions. I have had trouble with finding my grand and g-grandparents who immigrated in the early 1920s from Cuba, but understanding the naming traditions has opened new paths into my research.

LikeLike

This blog on naming conventions in different countries and cultures makes me think of a related name issue that can hinder genealogy research: the fact that both family names and given names were often mis-transcribed or intentionally “simplified” upon an immigrant’s arrival to the U.S. My reply is also a chance to thank Leslie for some very special research she completed for me. My maternal grandfather immigrated from Serbia, and all the living relatives knew him as “Steven.” As a teenager, years after his death, I questioned whether that was his actual given name, as to my ears it sounded very American. I was reassured that he had no other name, and my mother’s and my own research didn’t reveal anything different. It was only when Leslie researched my maternal grandparents on my behalf that she discovered that in fact his given name was actually “Stojan” (and the family name was spelled “Gjuric.”) The icing on the cake of this story is that well before I had this information, I chose the name “Stellan” for my son, which sounds almost identical to the Serbian translation of Stojan. And this is the magic of geneology – the ability to connect with the past in surprising ways that reveal something about the present! Thank you for your care and expertise, Leslie!

LikeLiked by 1 person